After something of a lull, AIDS Healthcare Foundation (AHF) president Michael Weinstein has revived his ever-the-skeptic public campaign regarding Truvada (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine) as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), publishing a critical editorial on the HIV prevention method in a major medical journal.

Over the years, AHF has run misleading and on certain points flat-out incorrect full-page advertisements about PrEP in gay newspapers as part of Weinstein’s years-long effort to chip away at Truvada’s image as a promising, or successful, means of combating HIV. While he denies being simply “anti-PrEP,” Weinstein has played the largely isolated role of the media’s go-to guy for negative sound bites about Truvada’s use as HIV prevention.

Now, five years since PrEP’s approval in the United States, Weinstein has returned to the fore, with an editorial in the prestigious journal AIDS in which he and a pair of AHF scientists dismiss Truvada as a mere “boutique intervention” against HIV, one that wreaks collateral damage on society and offers limited benefit in exchange.

The principle target of the AHF coauthors is the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). AHF has long slammed the federal agency for its failure to contain a fast-rising sexually transmitted infection (STI) epidemic and, on the HIV prevention front, for shifting its focus away from condom promotion and toward the use of PrEP and antiretroviral (ARV) treatment to prevent HIV (known as biomedical prevention).

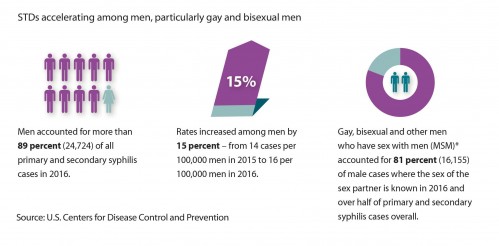

Graphic about syphilis among men in general and MSM in particular from the “2016 STD Surveillance Report”cdc.gov/nchhstp

STIs are rising fast among MSM in the United States according to the CDC.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/2015 STD Surveillance Report

PrEP, these three argue, “has not had the positive impact anticipated by the CDC.”

The authors’ position that PrEP has had limited reach in certain high-risk subgroups does indeed have considerable merit, as does their conclusion that Truvada’s use among HIV-negative individuals likely contributes to an increase in sexual risk taking. They commendably sound the alarm about racial, regional and age-group disparities. Complex circumstances have restricted the powder-blue tablet’s awesome power to prevent HIV—they do acknowledge PrEP’s high, adherence-based efficacy—from key demographics at greatest risk of the virus.

But by and large, the editorial is compromised by unsound logic, the cherry picking of evidence and the tendency to ignore important granular details about HIV infection and PrEP-use trends. Keen to highlight a lack of data proving definitively that PrEP has succeeded in preventing HIV on a grand scale in the United States (very challenging to prove in real-world settings), the essay all but ignores the numerous benefits of PrEP that have nevertheless become increasingly apparent in recent years.

These benefits extend beyond the medical realm and include the reduction of stigma toward people living with the virus as HIV-negative individuals reevaluate their attitudes toward partnerships across the HIV-status divide, as well as mitigated anxieties about and increased enjoyment of sex among those taking Truvada for prevention. Additionally, the routine STI testing that accompanies a PrEP prescription provides an excellent opportunity to rapidly diagnose and treat STIs.

Mitzy Gafos, MsC, PhD, describes to attendees of the 9th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science in Paris (IAS 2017) the psychosocial benefits of PrEP among British MSM in a recent study.Courtesy of Benjamin Ryan

More on PrEP’s psychosocial benefits from Mitzy GafosCourtesy of Benjamin Ryan

“Eradicating HIV transmission is a goal shared by us all,” the AHF essayists state, allowing that “PrEP clearly has a role in selected populations.”

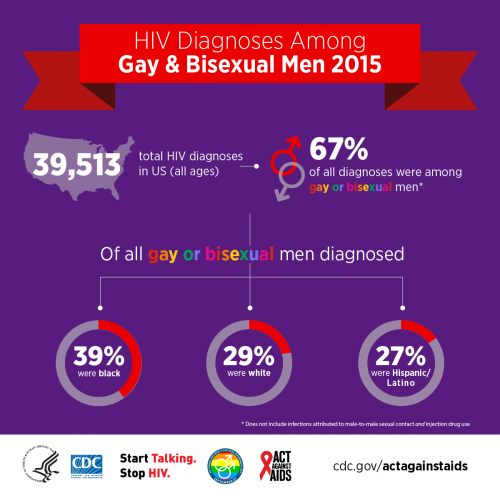

This admission notwithstanding, the editorial makes no explicit reference to men who have sex with men (MSM), who are both the chief candidates for PrEP and apparently make up the vast majority of its users. In their opening paragraph, Weinstein and his coauthors recognize the recent decrease in HIV infection rates in the United States and then rightly stress how various populations remain at disproportionately high risk for the virus, mentioning racial minorities, adolescents and young adults, and Southerners—but not a word about MSM. In fact, MSM, who constitute an estimated 70 percent of new diagnoses, account for the majority of infections in those three subcategories. Thirty-nine percent of HIV diagnoses among MSM are among African Americans, and an estimated 11 percent of young Black MSM in Atlanta contract HIV annually.

HIV infection trends in the United States according to the CDCCourtesy of CDC

Supporting their assessment that PrEP “implementation has been poor, particularly among the most vulnerable populations in the United States,” the editorialists point to the CDC’s estimate that 1.2 million U.S. residents are good candidates for PrEP. According to the essay’s implied logic, the fact that 125,000 people were on Truvada for prevention according to a May 2017 report indicates that only about 1 in 10 people at high risk for HIV are actually on PrEP. (The PrEP-use figure continues to rise, a trend AHF acknowledges, and climbed to 136,000 by midsummer 2017, presumably after their essay’s submission.)

The number of people found to have started PrEP per quarter in the pharmacies surveyed. (“TVD” is short for Truvada.)Mera, Magnuson, Hawkins, Bush, Rawlings and McCallister, Gilead poster presentation, IAS 2017.

The AHF group leaves out two key facts in this particular equation about PrEP’s reach: 1) various analyses have indicated that the vast majority of PrEP users are MSM; and 2) the CDC estimated that 492,000 of the 1.2 million PrEP candidates are MSM. In other words, the essay’s authors have used an overly broad denominator to give the false impression that PrEP is used by only a disappointing fraction of those at risk. Granted, many MSM PrEP users may be the worried well, that is, those at low risk for HIV and therefore not a part of that group of nearly half a million high-risk individuals. But research indicates that MSM at higher risk for HIV are in fact more likely to take PrEP than those who engage in lower-risk sexual practices. So it stands to reason that a sizable proportion of MSM on PrEP are in fact evading HIV infection as a result.

Weinstein, Yang and Cohen’s argument that PrEP’s impact is relatively minimal is further compromised by the fact that Truvada’s use for prevention is highly concentrated among MSM in various major urban areas with high HIV rates, notably San Francisco and New York City. This fact likely positions PrEP to deal a major blow to transmission of the virus in these individual, citywide epidemics. It’s probably already happening.

A 2016 photo of Demetre Daskalakis, MD, MPH, who at the time was New York City’s assistant commissioner of the Bureau of HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control at his office, alongside a poster from the city’s HIV prevention campaign, which promoted PrEP useBenjamin Ryan

The New York City subway, 2016Benjamin Ryan

As they say, all public health is local.

A just-released report from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene indicates that PrEP use in the metropolis increased 10-fold, or 27 percent per quarter, between 2014 and 2016. Meanwhile, San Francisco’s recent HIV surveillance report showed a plunging HIV rate. PrEP is likely contributing to this effect in the Bay Area city, along with increased rates of HIV testing and fully suppressive ARV treatment. (Keeping HIV at an undetectable level means the risk of transmission is effectively zero according to scientists’ assessments of the cumulative findings from three major studies.)

In the green boxes, the larger figure is the rate of prescriptions per 100,000 patients. The equation below that is the number of prescriptions divided by the actual number of patients. The 1.27 figure is the 27% per quarter prescription rate increase.Salcuni et al, NYC DOHMH: https://idsa.confex.com/idsa/2017/webprogram/Paper63138.html

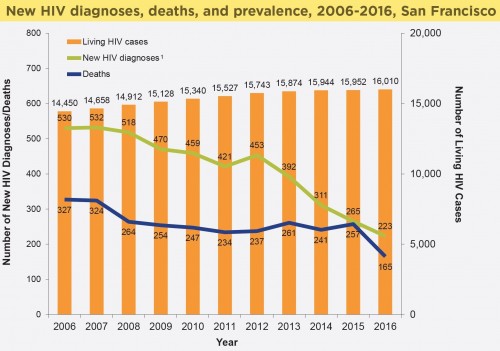

San Francisco’s HIV epidemic stats between 2006 and 2017. Note the considerable drop in HIV diagnosis rates beginning in 2012.San Francisco Department of Public Health

Kaiser Permanente Northern California recently reported that among the health system’s 5,000 or so patients who took PrEP through February 2017 and spent an average of one year on Truvada, none have tested positive for HIV while receiving a Truvada prescription. This perfect track record among an almost entirely male population holds true even as these individuals have contracted STIs at a very high rate—a strong indication that they are at considerable risk for HIV and that they have mitigated this risk through good adherence to PrEP. However, as Kaiser has been keen to point out, a handful of those patients who declined PrEP or stopped taking it have contracted the virus.

C. Bradley Hare, MD, the director of HIV care and prevention at Kaiser Permanente Medical Center in San Francisco in an exam roomBenjamin Ryan

Although Weinstein and his coauthors do refer to Kaiser’s PrEP data, as an example of what they categorize as the relative paucity of data on real-world use of Truvada for prevention, they apparently had on hand only an older report that included data on just 850 cumulative years of PrEP, compared with about 5,000 cumulative years in the new report.

The AHF group laudably warns that only an estimated 10 percent of PrEP prescriptions are written for African Americans, who make up nearly half of all new infections. Data from numerous sources, including the recent New York City analysis, have repeatedly indicated that PrEP isn’t catching on among Black MSM, despite their staggering HIV rate. And as the AHF editorial points out (without mentioning MSM), use of Truvada for prevention is disproportionately low in the South, the U.S. region where the need for an HIV prevention game-changer is the greatest.

Racial breakdowns of PrEP uses among men and women (“TVD” is short for Truvada.)Mera, Magnuson, Hawkins, Bush, Rawlings and McCallister, Gilead poster presentation, IAS 2017.

Breakdown of those who have started PrEP according to age and sex through 2016 (“TVD” is short for Truvada.)Mera, Magnuson, Hawkins, Bush, Rawlings and McCallister, Gilead poster presentation, IAS 2017.

CDC.gov/actagainstaids

In perhaps their most glaring flub, the AHF writers inaccurately convey the protocol involved with taking PrEP “on-demand,” whereby an individual is instructed to take Truvada only on the days surrounding sex. Suggesting, contrary to research findings, that adherence to the on-demand protocol may prove inadequate, the authors proceed to cite as supporting evidence the finer details of recommendations for taking Truvada according to the daily protocol. They refer to researchers’ estimates that to best protect against rectal transmission of HIV among those following a daily-dosing PrEP protocol, a week of Truvada is required to reach drug levels conferring maximum risk reduction, as well as a four-week tail after the final potential exposure to the virus. But on-demand PrEP, which scientists have become quite confident is highly effective (participants in the French IPERGAY trial of the protocol did generally adhere well; the protocol lowered their HIV risk by 86 percent), involves taking a double dose of Truvada two to 24 hours before anticipated sex, followed by one pill each 24 hours after sex if it occurs. There is no required week lead-in time or four-week denouement.

Jean-Michel Molina, MD, of the Hôpital Saint-Louis, in Paris and head of the IPERGAY trial, speaking at IAS 2017 in Paris Benjamin Ryan

To suggest that adherence to daily PrEP in the real world may be poor, Weinstein and his colleagues point out that the results of clinical trials may not translate well into real-world practice—a common, and often fair, criticism of such scientific research. The initial PrEP studies were conducted in “idealized conditions,” they write, with “extensive counseling and close clinical follow-up that do not occur in a busy clinical practice.” The AHF authors’ implication is that the study design of PrEP trials, including the so-called demonstration projects that sought to evaluate real-world use of Truvada as prevention, buttressed adherence to PrEP in a way that real-world practice typically does not.

But this argument ignores the larger social context in which studies such as iPrEx (published in 2010) and its open-label extension (published in 2014) were conducted versus how PrEP is used in 2017. Giving PrEP to high-risk MSM before it was approved (as in iPrEx) and before it began gaining popularity among the demographic (as in iPrEx OLE) meant that participants were likely not exposed to the kind of positive peer pressure that has since placed PrEP at the center of the sexual landscape in many gay meccas.

Today, with the pervasive chatter about PrEP in the MSM community—or the white MSM community, more specifically—men receive constant reminders that PrEP is highly effective and that effectiveness depends on adherence. (The iPrEx participants didn’t even know whether PrEP would work.) In short, PrEP has increasingly become a social norm. In fact, signs largely suggest that PrEP adherence in the real world is dramatically higher than in clinical trials. As Weinstein has long been fond of pointing out, those study participants had troublingly low levels of adherence to the daily Truvada regimen.

A 2016 ad for PrEP in West Hollywood created by the LA LGBT Center is an example of PrEP-related messaging toward MSM, the emotional benefits of PrEP, as well as the mindset that likely leads to risk compensation.Courtesy of the Los Angeles LGBT Center

The AHF essay also overdramatizes the concerns about PrEP’s contribution to the development of drug resistance, falsely claiming that “data to address this point are unavailable to date.” According to a 2015 analysis of a major clinical trial of PrEP, drug resistance for the most part developed just among the few participants who tested false negative for HIV before starting PrEP. There were only rare cases of the development of drug resistance among individuals who contracted HIV after receiving PrEP (they were likely adhering poorly at the time they acquired the virus) and then taking Truvada for a period.

IPrEx’s lead researcher, Robert M. Grant, MD, MPH, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, and Teri Liegler, PhD, an associate professor at UCSF, wrote in an editorial accompanying that 2015 paper on drug resistance: “Fear of drug resistance is now raised as we consider rolling out PrEP.” But the scientists qualified this concern by stressing, “Fomenting fear of drug resistance is also misguided if it distracts us from fear of HIV itself, by far the greater threat to human health.”

Robert Grant at the 2016 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in BostonCourtesy of Benjamin Ryan

The AHF writers’ concerns about PrEP’s contribution to increased sexual risk taking are certainly valid but should be considered within a larger context than the essay provides. Research has indeed finally started to indicate what has long been obvious to many gay men: that at least some MSM reduce their condom use after starting Truvada for prevention. However, whether such behavioral shifts drive up STI rates is debatable; in fact, the opposite is likely true according to the CDC.

The CDC recently published a mathematical modeling study that projected that even if PrEP use does lead MSM to dramatically lower their use of condoms, the routine STI screening they receive as PrEP users will drive down overall rates of gonorrhea and chlamydia. Indeed, PrEP studies have generally not seen significantly rising STI rates. Recent evidence out of London may provide real-world support to the CDC’s theory. As PrEP has exploded in popularity among attendees of the English capital’s main sexual health clinic, 56 Dean Street, gonorrhea rates have actually fallen (along with HIV).

The 56 Dean Street clinic in LondonBenjamin Ryan

Of course, there is always the thorny subject of money when discussing the benefits of pricey HIV medications. The AHF editorial questions whether the CDC was right to predict that PrEP is “cost-effective and scalable.” But researchers have conducted multiple analyses supporting PrEP’s cost-effectiveness—in some cases, Truvada as prevention may actually save money—when it is targeted to those at high risk for the virus.

On this cost-effectiveness count, the AHF essay’s validity suffers considerably from ignoring specifics of the use of PrEP among MSM. The PROUD study of PrEP use among British MSM, which was structured to mimic real-world use of PrEP as closely as possible, suggested that Truvada as prevention can have a major impact on a public health scale—it reduced participants’ overall HIV rate by 86 percent. The study, published in 2015, also showed strong evidence that providing Truvada to such a high-risk group of MSM would be financially sound. The investigators found that just 13 participants would need to take Truvada for one year to prevent one new highly expensive, lifelong HIV infection among them.

The head of the PROUD study, Sheena McCormack of University College London (UCL) at IAS 2017Benjamin Ryan

More than any other PrEP study, PROUD dealt a blow to one of Weinstein’s primary lines of attack against PrEP: that Truvada as prevention will not significantly lower overall HIV rates to an extent that would justify its costs and counterbalance other potential negative effects. In fact, reversing a longstanding upward trend, the HIV diagnosis rate among MSM in the United Kingdom dropped an astonishing 21 percent between 2015 and 2016, just as PrEP and HIV testing rates have soared and a greater proportion of those living with the virus have gone on ARVs. At 56 Dean Street, which diagnoses one in nine HIV infections in the United Kingdom, the monthly diagnosis rate has plunged 80 percent during the past two years.

56 Dean Street’s monthly HIV diagnoses (blue line) and monthly HIV tests, January 2015 through September 2017Chelsea and Westminster NHS Foundation Trust

Such signs of success notwithstanding, PrEP’s reach in the United States remains, according to numerous sources of evidence, largely limited to one cross-section: white MSM older than 25. This inconvenient truth highlights the overall tragedy of medical and public health disparities that keep African Americans lagging behind on myriad related fronts.

The primary pressing question about PrEP’s place in society going forward is whether the vast, interconnected engine of HIV research and advocacy that promotes Truvada’s use among those at risk for HIV can address such racial inequities and ultimately succeed in controlling the epidemic across the board, especially among those who are traditionally disenfranchised.

Whether AHF will ever get on board with helping to reduce such inequities, instead of maintaining what amounts to a stubborn denialist’s stance toward PrEP, appears unlikely as long as Weinstein remains at the helm.

AIDS Healthcare Foundation’s booth at the IAS 2017 conference adhered to the organization’s tendency to highlight a glass-half-empty perspective on the epidemic.Benjamin Ryan

To read an AHF press release about the essay, click here.

Benjamin Ryan is POZ’s editor at large, responsible for HIV science reporting. His work has also appeared in The New York Times, New York, The Nation, The Atlantic and The Marshall Project. Follow him on Facebook, Twitter and on his website, benryan.net.

5 Comments

5 Comments